Are you a subject, a citizen or a sovereign? Your answer to that question says a lot about who you think owns you, at least in the earthly sense.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about Eduardo Saverin giving up U.S. citizenship as Facebook goes public. He’s one of the founders of Facebook, so he’s becoming incredibly wealthy because of Facebook’s initial public offering. By living in Singapore and giving up his U.S. citizenship, Saverin is going to save millions of dollars now and save his heirs possibly billions of dollars by avoiding U.S. estate taxes later.

Saverin told the New York Times, though, that his move isn’t about saving money.

“This had nothing to do with taxes,” Saverin told the Times. “I was born in Brazil, I was an American citizen for about 10 years. I thought of myself as a global citizen.”

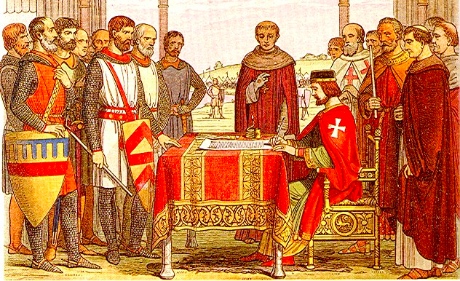

In 1215, King John of England signed what came to be called the Magna Carta. (The full name in English was “The Great Charter of the Liberties of England, and of the Liberties of the Forest.”) The English lords accepted that they were subject to the king, but they tried — sometimes unsuccessfully — to get kings to limit their absolute power over them.

Although there had been other attempts to limit the king’s power, the Magna Carta was the document that survived and came to be seen as the turning point. Before that, the “divine right of kings” was generally seen as almost absolute. After that, the king’s power was somewhat limited, but the king still ruled. And that’s the real point: The king was still sovereign.

As classical liberal ideas flourished in the 18th century, the idea came to be accepted that the people themselves were sovereign. There was no need for a king. No king had no special right to rule the people. The people — collectively — were considered to have the right to rule themselves.

People living under a king were subjects. People living under the new kinds of democracies or republics that sprang up — starting with the United States — were no longer subject to the rule of a king. Instead, they were citizens of a nation. They were collectively sovereign.

This was a great improvement over the old system, in some respects, I suppose. It’s easier to hope for fair treatment from fellow citizens — people you could theoretically see as equals — than it is to hope for an individual sovereign to treat you fairly. But you still had to live your life according to the rules of the majority of people. (I’m not going to get into details about the differences between republics and democracies.)

But even under the new systems, people were subject to the whims of their fellow men. Under the old system, the king owned them. Under the new system, everyone sort of owned each other. It was supposed to be a vast improvement, but it didn’t make people free.

Today, people believe that we owe things to one another. We’re told there’s a “social contract” that somehow magically requires us to obey the decisions of our fellow man — as embodied in the state, of course. We’re told that decent people owe support and obedience to the state — and that those who become financially successful have a moral obligation to hand that money over as ordered.

As Saverin has dumped his U.S. citizenship, he’s been criticized for it. Here’s an article that lays out the case that he pretty much owes everything to us — so he owes us that money. It’s breathtakingly collectivist in attitude, but when you think about the entire democratic system, it’s a form of collectivism — just with a nicer face.

Few people still see themselves as true subjects of a monarch today. Those people believe, though, that the king or queen owns them. Most people today see themselves as citizens of one country or another. Those people believe that they are owned by their fellow citizens (and that they also own them). They believe they jointly have power over each other.

But what if you believe you own yourself? You can’t be a subject. You can’t be a citizen — not even a “world citizen.” Instead, you’re a free man or free woman. You’re a sovereign.

But what if you believe you own yourself? You can’t be a subject. You can’t be a citizen — not even a “world citizen.” Instead, you’re a free man or free woman. You’re a sovereign.

A sovereign is “one possessing or held to possess supreme political power or sovereignty” or “one that exercises supreme authority within a limited sphere.” If you own yourself — in the civil sense — you don’t grant political power to anyone else to rule over you. And if you own yourself, you exercise supreme authority over your own life and property.

Eduardo Saverin is certainly doing the smart thing to get his money out of the clutches of the government of this country, but he’s not giving the correct answer when he says he’s a global citizen. If he had as much understanding of the world as he has wealth, he would tell the interviewer that he doesn’t recognize the legitimate right of the U.S. government to steal his money, so he’s arranging his affairs in such a way that the least possible amount can be stolen.

Some people would call him greedy for this, but it has nothing to do with greed. It has everything to do with being a sovereign — a free man — and declining to stand by while looters take your property.

You might see America as your homeland — or Argentina or Spain or Russia or a thousand other places. But whatever you see as your home, determine to see yourself — at least in your own mind and heart — as a sovereign individual. If you don’t do that, you’re admitting to yourself that you believe someone else owns you.

UPDATE: After surgery, maybe I’ll eventually start feeling better

UPDATE: After surgery, maybe I’ll eventually start feeling better Why do we create families? It’s a ‘matter of the heart,’ not head

Why do we create families? It’s a ‘matter of the heart,’ not head What if our craving for dopamine drives our desires and addictions?

What if our craving for dopamine drives our desires and addictions?